What does a substance as seemingly innocuous as milk have to do with the political geography of British imperialism in Burma? Probably not a question at the forefront of your mind. But milk drinking, it turns out, was a marker of cultural difference. It was also a product the making of which was bound up with tensions around immigration.

Who drank which creature’s milk mattered to British imperial writers in the colony. A definitively mammalian product for nourish young creatures, the consumption of milk was a form of interspecies intimacy. As such it, was subject to certain taboos and framed by historically contingent cultural understandings. It was commented that Indian ‘martial races’, such as Punjabi Sikhs, drank milk and ate cheese and thus were muscular and manly. In contrast, it was claimed Burmese Buddhists did not drink milk because of their sympathy for animal life. Some writers went further, recounting in disgust apocryphal stories of Burmese women nursing orphaned animals. These descriptions of milk drinking fed into British representations of Burma as a place distinct to India and behind Britain in the development of decorous sensibilities and secular thinking.

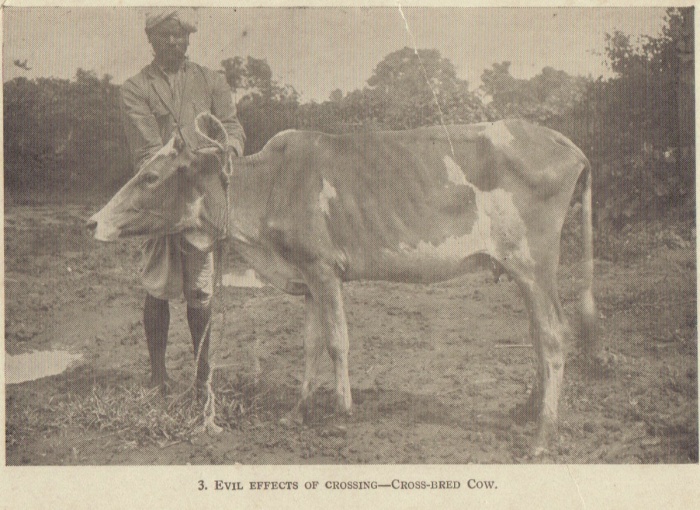

At the same time colonial officials worried about the plight of plough cattle in the colony. By the end of the nineteenth century Burma was the largest rice producer in the world. The cultivation of this staple was dependent upon the labour of oxen who ploughed the fields, provided manure and transported people and rice across the colony. Officials believed that local Burmese breeds of ox were hardier than those found in India, although both were of the species Bos Indicus and neither had been subjected to the same intensity of anthropogenic selective breeding as bovine livestock in Europe. As result, officials became concerned that the migration of dairy herds from India were a threat to the Burmese ‘breeds’ of cattle. These Indian herds were said to spread diseases and to promiscuously mate with local oxen leading to a degeneration of local plough cattle. The measures the colonial state put in place to rectify these supposed problems were coterminous with similar policies put in place to regulate the movement of Indian people into the colony.

In an article published in the Journal of Historical Geography, I argue that both the cultural observations made about dairy consumption and the state controls put on Indian dairy herds were part of a wider naturalisation of Burma’s political geography – a mapping that was always and remains contested, complex and contingent. But how did milk even come to emerge as a subject to study? Certainly, I did not ever envisage that I would be engaged in uncovering a history that, taken at face value, sounds so esoteric and niche. The topic came into focus only after I had started a new research project into the history of animals in colonial Burma. By decentring humans as the default starting point of my study, I have found myself reading archives in different ways in order to tease out the records in which histories concerning myriad other creatures resided. This was particularly apparent when I went back through the annual reports of the Rangoon Lunatic Asylum. I had scoured these reports several years earlier for an article on colonial psychiatry, but during this research I had entirely missed the fact that the institution had its own dairy herd with over forty heads of cattle – despite the asylum’s chronic overcrowding. My turn towards animal history has not so much been to put animals into history, but to recognise the ways in which I had previously ignored and overlooked their presence.

Jonathan Saha is an associate Professor at the University of Leeds specialising in the history of colonial Burma. His blog Colonizing Animals looks at the history of beasts, British imperialism and Burma.